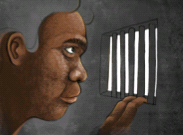

There is a glaring omission in the discussion of Indigenous deaths in custody. It is the influence of widespread hearing loss contributing to the over representation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system.

The extent of the ear disease that leads to Indigenous people’s hearing loss is a well-known health issue. But how this hearing loss influences communications with police, judicial and corrections staff is not.

This article by Damien Howard and Jody Barney, writing for The Mandarin.

When Indigenous people with hearing loss talk to police or others in the justice system they may:

- be seen as non-compliant, or defiant when they misunderstand what is said to them

- are more likely to be arrested when they have difficulty answering questions and ‘explaining themselves

- are often seen as aggressive when they ‘talk loud’, because of their hearing loss

Indigenous prison inmates with hearing loss describe their experiences, starting with police and moving on through the justice system:

“I get in trouble from police when I can’t hear what they talking”

“Can’t hear them police or them court man”

“Several of the guys told me that, because of their hearing loss, they often did not understand what guards wanted them to do, so they were in constant strife with the guards in the prison”

The reluctance of some officers to repeat instructions can make it hard.

“I get pissed off when people won’t repeat. Officers will say, “I’ll tell you only once”’

Others report the isolating effects of their hearing loss and its impact on their psychological and emotional wellbeing.

‘I feel isolated’

‘I feel scared when I can’t hear’

‘I feel angry. I sit in my room, it’s just easier’

‘I feel no good, can’t join in. I go to my room a lot and shut the door’

‘I try and concentrate on the conversation but I end (up) in my room’

‘I can get paranoid about things when I can’t hear’

Being shamed in public makes it worse.

‘I feel shame when I get into trouble in front of others’

The self-isolation often mentioned as a means of coping with the problem of communicating in a prison shows detention involves a harsher punishment for those with hearing loss.

The 2010 “Hear us – Inquiry into hearing health in Australia” carried out by the senate standing committee of community affairs made some important points and recommendations in the chapter on Indigenous hearing loss.

“Poor communication at a person’s first point of contact with the criminal justice system can have enormous implications for that person.” (page 148)

“It is probable that the distinctive demeanour of many Indigenous people in court is related to their hearing loss. Where this is the case there is a very real danger that the courtroom demeanour of Indigenous people (not answering questions, avoiding eye contact, turning away from people who try to communicate with them) may be being interpreted as indicative of guilt, defiance or contempt.” (Page 141)

The ‘Hear Us Inquiry’ also made important recommendations which have not been implemented. So too a recommendation of the Australian Medical Association’s 2017 Indigenous health report card that all people engaged with Indigenous people should participate in ‘hearing loss responsive communications training’ to help them work with the many Indigenous people with hearing loss. To our knowledge no police or corrections staff in any jurisdiction have received this type of training.

There remains scant information on the effects of hearing loss on Indigenous people in the criminal justice system. The different research sectors have consistently ‘duck-shoved’ responsibility from one to another.

- The criminal justice research agencies have seen it as a health issue

- The health research agencies have seen it as a criminal justice issue

Other barriers to conducting research into this topic have also been evolving.

In recent years there has been increasing commonwealth delegation of key decision making on the allocation of research funding to researchers and a few large research organisations. Letting researchers decide what should be funded introduces a profound bias against research into new topics.

Most current decision-making formulae for allocation of funding require that applicants must have strong research track records to succeed in gaining a grant. In a field where there has been minimal research, such as this one, no interested researchers can have a sufficient credible research history to obtain a grant. It’s a ‘Catch 22’, if something hasn’t already been researched, it is likely no interested researcher can get funding to do research on it, no matter how important the topic is to community interests or justice outcomes.

The seemingly innocuous idea that only the most experienced researchers should receive research funding is akin to reinstating seniority over merit in job selection in the public service and calling it progress.

It’s interesting to note that the available information on the consequences of Indigenous hearing loss in the criminal justice sector has been generated largely by public servants, not researchers. In the 2011 Senate report, it was public servants, under the direction of politicians, who collected and presented information from those working in the field on the observed impacts of hearing loss among Indigenous people in the justice system. No formal research had ever done this. In the nine years since that report no formal research has done anything similar.

What is arguably the most critical research to date in the area was conducted by public servants in the corrections branch of the NT government. In 2010 at their own initiative they began testing of inmate hearing levels in The NT and found that an astounding 94% had a significant hearing loss. Despite increasing concern about over representation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system, no significant further research in this area has occurred. Rather, research has taken place into ‘the usual suspects’ of research topics. It is like a justice system that only allows those convicted of past crimes to be investigated as possible perpetrators of new crimes.

The absence of information and lack of action on existing multiple recommendations over decades represent the repeated failure of mainstream systems.

Meanwhile, Indigenous people with hearing loss still experience the same problems when in contact with police, in courtrooms and in detention. They are still misunderstood and misjudged. The risk remains that they may be hurt or die confused and distraught, angry and isolated. They experience an invisible ‘communication based profiling’ as well as incarceration being more profoundly isolating and distressing than for others.

These same mainstream institutions also continue to fail the front line police and corrections staff. These workers remain ill-equipped when they engage with the many Indigenous people with hearing loss in the course of their work.

Perhaps something may change when a police or corrections department is held responsible for their decades of culpable neglect, when a hapless policeman or corrections officer, who has not been adequately equipped for their work, makes a poorly informed decision which ends in tragedy.

Authors: Dr Damien Howard is a psychologist and Jody Barney is a Deaf Indigenous community consultant. Each has worked for over 30 years towards understanding and mitigating the impacts of widespread hearing loss among Indigenous people.

From The Mandarin